After the birth of a child (Chinese superstitions)

Chinese (traditional) superstitions after birth. Excerpt from "Manual of Chinese superstitions, or Small indicator of the most common superstitions in China." By Fr. Henri DORÉ, SJ (1859-1931). Distributed by chineancienne.fr under license CC-by-nc-sa.

On the third day after the birth of a child, a double ceremony is required:

1° Prostration to the Spirits of the bed. On that day, a rooster is placed near the bed of the woman who has given birth, who lights candles and makes prostrations in front of the rooster, ki, the same sound as ki, pomp: it's a play on words. This rite is called: p'ai Tch'oang-kong Tch'oang-mou, to greet the two Spirits of the bed, male and female. In case the woman who gave birth was ill, this ceremony would be performed by the midwife, si-p'ouo, vulgo tsié-cheng. The rooster is immolated.

2° Si-san-tchao. The bath of the third day. The child is placed in a warm, variously scented bath with mugwort and hoai branches. We throw in a few coins, and some auspicious fruits, to wish him happiness and long life. The boys are dressed in red clothes after the ritual bath; as for the girls, they are dressed in green clothes. On this occasion, various superstitious customs are practiced according to the diversity of the countries; all aim to ward off evil influences, pi-sié, and to attract the five happinesses upon the newborn. Relatives and neighbors offer the child's mother tsao‑lao and kang‑kao cakes. She should not take any other food for the first three days after giving birth. This time expired, people from outside can no longer enter his apartment, it would be harmful! In Kiang-nan, the mother drinks three times a day a decoction of mugwort, ngai-tsao, mixed with red sugar, hong-t'ang. On the third day, the child's horoscope is drawn, and the diviner determines the dangerous customs he will have to pass; he indicates the means to be taken to get him out of trouble. The diviner relies mainly on the day and time of birth to draw omens. On that day we also thank Song-cheng niang-niang.

Man‑yué, at the end of the month after giving birth. When the month is over, everyone comes to offer their congratulations and their presents, the happy mother can also cross the threshold of her room. Among the presents are breads on which the character hi, joy has been printed. It is a rejoicing, a very lawful family celebration provided that it does not interfere with other pagan practices.

Hiang-t'an. If, before the end of the month following childbirth, the mother entered a neighboring house, it would be an omen of misfortune. The remedy: in the countries of Ngan‑hoei, people resort to vaporizing hiang‑t'an vinegar. Vinegar is poured into a cast iron crucible, heated to red heat; the acid smell of vaporized vinegar drives away harmful influences.

The first outing. The past month from the day of birth, the child's head is shaved. This done, the paternal uncle takes the child in his arms, while the husband of the maternal aunt takes an umbrella and extends it over the child. Both of them walk him thus on the street of the town or the village. He will never be afraid again!

Kouo-k'iao The same day, the father or the mother take the child in their arms; in one hand they hold ╓10 sticks of lit incense and cross a bridge, repeating twice: Ni-p'ou p'a! Do not be afraid ! The evil elves are particularly to be feared near bridges.

Keou-mao-fou. After having shaved the child's head, and before taking him out, care is taken to mix a lock of his hair with dog hair; the whole thing is enclosed in a sachet, which is sewn onto his clothes. The child equipped with this amulet can be carried outside, nothing to fear, neither for him nor for the others.

The usual superstitions about children are very numerous and very varied. Here are some of the most common.

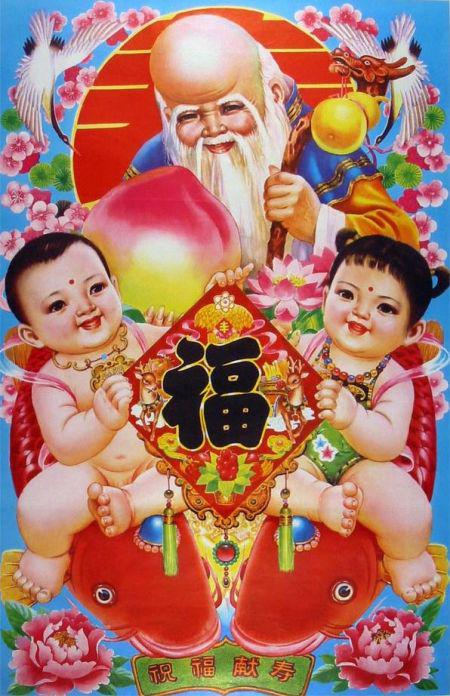

Poussahs on the cap of the children. The pagans like to adorn the caps of their children with different statuettes of pushahs. On either side of the cap, above the ears, are three or four statuettes of Maitreya (Mi-lei-fou), the future Buddha. The Eight Immortals, Pa‑sien, on each side. The two statuettes of Houo Ho eul his, depicting joy and wealth. Statuettes of the Crazy, Lou, Cheou Spirits, happiness, dignities, long life. Various inscriptions: Koan-cha-k'ai-t'ong, Ghost customs open. Ch'ang-ming fou-koei, Long life and wealth. (It's more of a wish.) A tiger's head on the central medallion. The image of the god of happiness, Fou-chen. All these ornaments are usually silver or even vermeil.

Eul tchoei-tse, pendant earrings. The ears of little boys are pierced like those of little girls, but they are given only one pendant. Some claim that it is to deceive the malevolent devils. who will be deceived about the sex of the child. The evil goblins, it is believed, are especially angry with boys. More often, the ear pendant takes the form of a massive silver or even gold weight. A weight is heavy, the evil devils will not be able to lift the child and carry it away 5!

Pi-k`iuen, the curl of the nose. The buffaloes and oxen wear a loop in their noses, by this means one can keep them at home, prevent them from escaping. In the same way the loop passed in the nose of a child will make it possible to chain it to life, and the diseases or the elves will not remove it from the affection of its parents.

T'ien-tschou, the red dot on the forehead. Word for word: the cinnabar of the sky. Red is the color of yang, therefore of happiness, of life. Children are marked with a red dot on the forehead, on the cheeks, as a pledge of happiness, long life and the protection of heaven. On the 5th of the Ve Moon, in the morning, a mixture of brandy and phosphorus is made, with which one rubs the head, the temples, the ears of the children. It is an exorcist composition against the Ou-tou, the five venomous. It is, in Chinese, a pi-sié, exorcist talisman, especially if with this mixture we trace on their forehead the character wang, king, that is to say the Tiger-king.

Hiang-k'iuen, the necklace. Silver circle around the child's neck. The goal is to encircle it to life. In coarse circles, it is an omen that the child will be as easy to bring up as a small dog; hence its common name: keou k'iuen. Sometimes the necklace is imposed by the bonze, who keeps the key. You will have to pay for this. Most often, parents and friends pay the price and offer a beautiful silver necklace for the newborn.

Jen kan‑fou, choose adoptive fathers. When there is every reason to fear for the life of a newborn baby, it is adopted by eight men from the family or the neighborhood. These eight men buy him a silver necklace and a padlock to close it. The day they put it around his neck is the souo-koan. That is to say, no elf will be able to harm it. Customs is closed! When the child has reached the age of 12, the eight adoptive fathers return and themselves open the padlock to remove the necklace; it's called: k'ai-koan, to open customs.

Lao-jen-koanIf the diviner recognizes that the child must go through the old man's customs, lao-jen-koan, there is only one way to save him from certain peril of death: it is to find an old man who consents to wear mourning; then the child will live.

Yu-in, the jade seal. A jade seal placed on a child's cap as a forehead medallion is a sovereign talisman against fear.

Tiger claw. For the same reason, silver or copper ornaments represent a tiger's claw. It is also a protective talisman against transcendent enemies.

Hou-lou, the gourd. A small gourd in copper, silver, or better carved in wood with the planks of an old coffin, is an effective talisman against illnesses. It depicts the Immortal Tchang Kuo-lao's medicine gourd, and Lao-tse's immortality pill gourd. This ornament is attached to the cap of children.

Song-hiang-k'iuen, the iron collar. When a stricken family sees all its children die, the parents take part in its pain, and offer, for the first boy who will be born, an iron necklace, forged with the nail of longevity which one sees fixed on the coffin of the dead. .

Pé-souo-cheng, the rope with a hundred threads. Cord passed around the neck of children, and which is intended to chain the newborn to life; it is a simple rope among the poor. It is an allusion to the capture of Maitreya by Lao-tse, who passed around his neck the mysterious cord given to him by Buddha 8.

Ts'ien-long, the string of sapeques. It is customary to hang around the necks of children a few sapeques threaded in a red cord. It is a pledge of wealth. The pagans hold on to it amazingly. Old sapeques from bright kingdoms are preferred. Sometimes the cord and the coins are placed on the altar of the Tch'eng-hoang before the necklace is placed around the child's neck. During the procession of Ch'eng-hoang, the Pé lao-yé carries sapeques suspended in his mouth, by a thread; these are particularly effective. These sapeques are called han-k'eou-ts'ien, when they have been suspended by a thread above the coffin, and introduced into the mouth of a deceased. The sapeques threaded in the stems of reeds forming the framework of the houses of paper, are collected with eagerness, after the combustion of these houses. The sapeques are given to the children, who hang them around their necks. These are just as many precious talismans.

Tai-souo, wear a padlock hanging from the neck. The padlock, silver or copper, of very different shapes, is suspended from a silver chain. The chain is passed around the child's neck; then there is nothing more to fear: he is chained to existence, he will not die. Multiple inscriptions or superstitious emblems are engraved on these padlocks. Sometimes the tao-che or the monks themselves pass it around the child's neck and keep the key, which is placed in an opening made on the back of the statues in the pagodas. The henchman of the Tch'eng-hoang, vulgarly called Mr. White, Pé lao-yé, carries in his mouth, suspended from cords, amulet padlocks, which are greatly appreciated by pagan families.

Pé‑kia‑souo, the padlock of the hundred families. Purchased by the contribution of all neighboring families, relatives friends, neighbors. It is more effective because it provides proof that everyone around is interested in the good health of this precious baby.

Pa-koa and superstitious medallions. Many children wear superstitious medallions of all shapes suspended from their necks, adorned with emblems or inscriptions of superstitious origin, when they are not essentially so. It shows, for example, : the pa-koa, eight trigrams; — the Animals of the Cycle; — talismans drawn by the tao-che and the bonzes; — figures of pousahs, etc. ...

Tchouo-tse, the girl's bracelet. In the country of Zang-zôh (Kiang-sou), little girls are too often doomed to the devil, and as a pledge of this shameful pact, they wear on their left arm, until the age of 13 or 14, the irons of the slavery. It is a small silver bracelet, closed by a padlock to which is attached a small chain of the same metal. Families less well off get a device of the same shape, but in copper. Often, the key of the small padlock is deposited in the belly of a large pousah. These awful wooden or mud nests are hollowed out inside, and a hole in their backs allows various objects to be placed there.

T'ao-ho-souo, padlocks carved from a flat peach stone, pan-t'ao. The peach is the fruit of immortality, served at the banquet of the Immortals, at the goddess Wang-mou niang-niang. Also mothers like to attach these little padlocks to the child's two feet. To bind them, they use the cord used to tie the braid of their hair. They believe that these padlocks will provide longevity to their children.

The doorbells. Many believe that the custom of attaching bells to the feet of small children was intended, in principle, to scare away evil spirits. Matter of intention!

Wear monk's clothes. Usually it's a promise. made to a pushah: "If you grant me a boy, I will dedicate him to you as a monk at your service, and he will wear monk's clothes. By exception, there is the routine, acting without thinking and by imitation of the common. Often the wish is conditional, the age of the child is fixed, when he can be redeemed by alms given to the monks.

Pé‑kia-i, to wear the habit of the hundred families. We go from door to door begging for a piece of cloth, and with these variegated and disparate pieces we make a coat for the darling child we want to preserve from death. How could he die, when so many people are interested in his fate 16 ?

Pé‑kia‑sien, the thread of the hundred families. We ask all the neighbors for a piece of thread, then from these multicolored threads we make a small pendant which we hang on the child's clothes. The idea is the same as the previous one, but the process is more simplified.

Pei-king. Tantric formulas are written on tiny notebooks, which are attached to children's belts after having asked the monks to recite these formulas. They preserve the child from misfortune and death.

Tchan-yao-kien, the funeral sword. The magic saber composed of sapeques or devil slayer saber. We hang it on the bed or on the wall; the devils frightened at this sight flee. This sword reminds them of the terrible swords of Tchang T'ien-che and Tchong K'oei.

The homicidal dagger. Any dagger previously used to kill a man thus becomes a transcendent instrument, capable of intimidating the devils. To prevent them from entering a room, simply hang it above the door.

The coffin nails. Nails from old coffins also become effective talismans to terrorize devils.

The sieve and the 3 arrows. The sieve is the thousand-eyed talisman called ts'ien-li-yen. The arrows are fixed on the sieve with this inscription: Ch'oan-yun-tsien, Arrows penetrating the clouds.

Bag of dog hair. A sachet containing dog hair, an onion, charcoal and sticks is hung near the cradle.

The child's father's panties. These panties hang from the column supporting the curtains of the bed. The belt should be turned down and the legs up. It is a pi-sié (or pi-hiong; others write pi) or exorcism.

Before sending the child to school. The fortune-teller is invited, who examines the eight characters, pa‑tse, of the child and calculates the favorable day for entering school. In a word, in all the principal circumstances of life the diviner gives a decision according to the pa‑tse; and after death they are written on the tablet of the soul.

At the age of 1 year. Choice of career. Various objects are placed in front of the child: abacus, brush, tools; according to the object he chooses, we augur his future profession.