The roundup of the greenback: the testimonies of Denise Kandel and Renée Borycki

These two women were children aged 5 and 8 when their fathers received a green ticket, delivered to their home by the French authorities. They were called to a meeting on May 14, 1941, at 7 a.m., like more than 6,400 foreign Jewish men then living in Paris and the Paris suburbs. More than 3700 will go there. They will be taken the same day to the internment camps of Pithiviers and Beaune-la-Rolande in Loiret. Many of them will be on board the first convoys leaving France for Auschwitz-Birkenau, in 1942. Eighty years later, the Shoah Memorial has just acquired 98 photos of the greenback roundup, most of them unpublished , the full report by a German photographer from the Propagandakompanie. Denise Kandel and Renée Borycki went to draw on their memory. Here are their testimonials.

Read also: "I would like something to remain" honors the work of the volunteers of the Shoah Memorial

Denise Kandel, born Bystryn, chooses French to talk about this period. However, she has lived in the United States since 1949, in New York, where, at 88, this sociologist and epidemiologist, professor at Columbia University, continues her research work. She looks back on her childhood spent in France, where she was born on February 27, 1933.

His childhood

I have images left that are not linked to each other. We lived in Colombes in the suburbs of Paris in a very small apartment. My universe in Colombes was the building, the school at the foot of the building, and the shops three streets away. My father, Iser, worked, he was an engineer and my mother, Sara, took care of the house, she knitted a lot. My parents arrived in France in the 1920s. They came from Poland, where Jews were not allowed to study. My mother told me that she had been spat on by young Polish men. My father left home when he was 17 because his father wanted him to be a rabbi, not him. My parents had applied for French nationality, but they were unable to obtain it. They only got it after the war.

The call for the greenback

I remember a big argument between my parents on May 13, 1941. My mother did not want my father to attend this summons. And my father was someone who thought that if we followed the rules, everything would be fine. He was always optimistic while my mother was always very pessimistic. She insisted a lot not to let him go, he was someone extraordinary, voluntary. But she failed to convince him and she went with her.

I had a brother who was five years younger than me, Jean-Claude. We both stayed at home that morning with the ban on going out. Then she came back to get a blanket and some clothes.

The internment of his father in the Beaune-la-Rolande camp

I have a clear memory of how my parents communicated. My mother used to buy gingerbread covered in cellophane. She would remove the cellophane, cut the gingerbread in half, pierce it to put a letter, in Yiddish I think, and rewrap it. I believe they had also developed some sort of coded language. If she wanted to send him money or other messages, she would buy a pair of shoes, she would hide these objects in the heel and she would say to him “my left foot hurts”. At that time, my mother spent her days in Paris, running from one office to another to try to get him out. She left me, at 8 years old, to take care of my little brother of 3 years old. She trusted me a lot. What we don't realize is how much children, even young ones, understand what's going on.

Escape

My father arrived at the camp on May 14, 1941, he escaped at the end of January 1942. My mother wanted him to escape earlier, but he refused because he was the barracks leader. He represented the interests of the internees with the authorities and he feared that the internees in his barracks would be punished in retaliation. My father had an ulcer, he had a stroke and was hospitalized outside the Beaune-la-Rolande camp. He ended up being convinced by his roommate. It is unclear when he escaped, possibly January 29 or 30. In a register in the archives, I found the trace of the distribution of the parcels to the internees and it is mentioned that that of Mr. Bystryn was distributed to the community because he was no longer there.

In Colombes, in our apartment, the police came. I believe the janitor was present. The policeman said to my mother “we are coming to get your husband”. She replied "but you know that he is interned in Beaune-la-Rolande". They searched everywhere, in the cupboards, under the beds. Of course, they found nothing. This is how my mother understood that my father had escaped. When they left, I don't know if it was the janitor or the policeman, who made a sign behind his back to tell us to leave. The next day we left the house.

Escape into the free zone

My parents had decided that they would meet in Saint-Céré, near Cahors. They had never been there, but I guess they knew it was an area where Jews could go to take refuge. They only got together with my mother in May or June. My father suffered from an ulcer which, a second time, would save his life. He had a new crisis. The surgeon who operated on him in Cahors was part of the resistance, his wife was Jewish. He kept my father six weeks in the hospital. He knew everyone.

Thanks to him, I was able to go, with my brother at first, to a religious boarding school, Saint Joan of Arc, with the agreement of the mother superior, Mother Marie Emilia. I was 9 years old. My brother could not stay after kindergarten because the primary school was not mixed. So the teacher, Yvonne Féraud, who took great care of us, hid him with her uncle and aunt, the bakers of the small village of Escamps. To protect me, my mother had decided to have me baptized. She came from Saint-Céré to Cahors to give permission to convert me. But when she got to the door, she couldn't go any further.

While I was in hiding at the Institution of Saint Joan of Arc, I lived in constant fear - fear that someone would find out that I was Jewish, especially since I could not participate in the communion of mass on Sunday; the fear that a gendarme or a German would come looking for me when someone opened the classroom door; the fear that my parents will be arrested, the fear of never seeing them again. I tried to talk as little as possible so that no one asked me questions. I was told that if one day the authorities came to get me, I had to hide ten meters from the classroom, in a tunnel built under one of these 13th century buildings. Each time I returned to Cahors with my children and my grandchildren, I wanted to see this place again, which I called the underground. It had such importance in my imagination! And today, I still don't know where it leads, it has since been blocked by a cement wall.

In May 1944, it was deemed too dangerous for me to stay with the sisters. One day, on the Cahors bridge, my teacher was approached by a woman who asked her if she knew me. She gave him a fake ID for me. I then went to Yvonne Féraud's parents in a small village near Toulouse, where I took care of the geese. I took the steps and Yvonne Féraud was able to be recognized as Righteous Among the Nations, her name is inscribed on the wall of the Shoah Memorial.

The return to Paris

The four of us were only reunited at the end of the war. We returned to Paris. We found our apartment in Colombes completely looted. My father got his job back as an engineer. His boss had been a collaborator, he rehired him and my father testified in his favor by saying that he had helped him by sending him part of his salary after his escape from Beaune-La-Rolande. During the war, in 1940 I believe, my parents had taken steps to emigrate to the United States. In 1949 they were still on the list and their applications were granted. There was then a great discussion. They finally decided that the whole family would go to New York, that they wanted the children to grow up in a Jewish environment, which was not the case in Paris. I never entered a synagogue until my marriage… It was a very difficult decision to make. When we arrived in New York, we had no money, my mother had to work as a maid, my father, who had given up a very good job in Paris, had difficulty finding work because his diploma engineer was not recognized. He died of pancreatic cancer in 1954. The heroine in all of this is my mother. She knew how to understand situations, how to apprehend problems. Still, she persisted.

-----

Renée Borycki: "After all this, it's hard to believe in God"

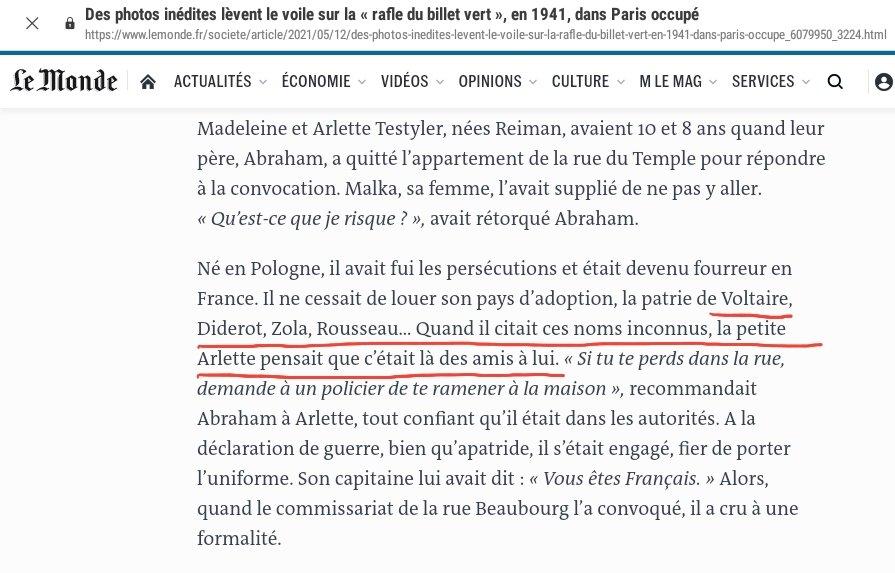

Renée Borycki, née Sieradzki, is recovering, but she receives us, with her son Alexandre, in her living room of her apartment in the 11th arrondissement of Paris, the district where she already lived as a child when the Second World War began. She was born on July 16, 1936. She was only five years old when her father, Mordka, received the greenback. With her mother, Bluma, she accompanied him on May 14, 1941 to the Japy gymnasium.

Beginnings of the war

I was little, but it marked me for life. I still don't understand how a five-year-old girl can be so marked by this era. As anti-Semitism grew in Poland, my parents, who had just gotten married, decided to come to France. My father left first, found a job as a hairdresser and Mum joined him. She started working, in sewing, with tailors. I am their only daughter. We lived on rue Faidherbe, in the 11th arrondissement. I remember a wonderful dad, who came home from work with his pockets full of candies and small toys. The few Jews in our neighborhood met very often at Mom and Dad's who were very sociable. I heard them all the time talking about the arrests, I didn't know what it was, but I understood that something dangerous was happening. When I asked why, Mom said "you won't understand my darling, it's because we're Jews". What did that mean for a five-year-old girl? I heard them talking day and night about the measures against the Jews, about these posts they were forbidden to exercise. Mom and Dad were crying. Mum said “maybe we should have stayed in Poland with the family”. Dad said, "No, it's worse over there." I heard that constantly. One of our neighbors had advised us to go to the free zone, but my parents could not afford it. My parents had been to the census in the fall of 1940. Mom always said that behind her, in the queue, there was a Catholic priest. She asked him what he was doing there, he said “I am a second generation Jew, I have to register”. In all my life, I have never been able to answer a census.

The roundup of the greenback

Tickets had been deposited from May 9th. One evening, everyone gathered at Mom and Dad's house. They started talking, they knew that Jews were going to be arrested. My father had applied to be a soldier, to enlist in 1939, but it had been refused. He said that he had to go to this summons to the Japy gymnasium, that he was honest, that he did not feel guilty of anything. We left early in the morning, the three of us, since no one could watch me. Dad was pushed inside by the French police. I stood on the sidewalk while Mom retrieved a list of essentials to pick up at home from an office. We both went there, we walked in silence, both impressed. She packed a small suitcase and we went back to the gym. Mom thought we were going to show her Dad. They just took the suitcase and his name from him and ordered him to leave. She asked 'but you take them away, what do you do?'. They didn't answer, they kicked. She assured me he would be back. We came home and the darkest period of my life began. Dad wasn't there, mom was crying all the time, she didn't have a job. We were locked up like wretches.

Pithiviers Camp

We were informed that Dad had been sent to an internment camp in Pithiviers. She had the right to see him once. She took me. She had brought food and a change of clothes. We were seated on the ground, separated from the barbed wire. Afterwards he was sent on July 17, 1942 to Auschwitz-Birkenau by convoy n°6, and there, needless to say, we never saw him again. And yet, he is among the survivors. He came back, in a sorry state, but he came back.

The Vel d’Hiv roundup

One evening, we heard the French police asking the guard to get a tool to break the doors, they had to put seals. We had no one to go to. Mum had gone up with me to some neighbours, a very nice young French couple, parents of a baby a few months old. They told us that they wanted to help us, but that they couldn't. Mom remembered that a cousin of Dad lived in Livry Gargan: they weren't arresting Jews there yet. The neighbor had first decided to "preserve the little one": he had arranged a sheet that communicated with the window so that I could escape. The police arrived. Our neighbor hid us under a blanket at his house, we could hear the police below putting seals on our house. We no longer had a home. The next morning, the neighbor asked us to leave, he didn't want to risk his child's life. Mom was wondering how to run away with me as everyone was being taken out into the street. The neighbor was tall, very slender, with a hat. With his distinguished look, he looked like the policemen of the time. So this gentleman suggested that he come out and walk behind us: “If we arrest you, I don't know you. If we have the chance to pass, we will see. We went like this to the Place de la Nation. It was black with police. I still remember these little children with their parents, the French police who brutally put them in trucks. It was July 16, 1942, my birthday. We boarded the subway, our neighbor accompanied us, always at a distance. At the Pantin church, he put us on a bus before leaving us.

A child hidden in a cubbyhole

We stayed with this cousin in Livry-Gargan for a while. She was mean, she exchanged the few jewels that my mother had been able to take for some food. I cried all the time at night, I was so hungry. As we were going out one day with mum and the children of the house, a Kommandantur car arrived. They arrested my cousin. With mom, we were wandering in the street, we didn't know where to go. She entered the caravan of the gypsy who read the lines of the hand, asked her if she knew someone who could welcome us, on the pretext that I had whooping cough. The gypsy took us to her mother. On the way, we again escaped arrest. The next morning, when the gypsy's mother realized we were Jewish, she chased us away screaming.

Again, we were on the street. A lady was watching us, she knew the cousin. She approached. We went up to her place, she made the decision to keep us. But she was scared too. She hid us in a cubbyhole with a folding bed, day and night. We stayed there for two and a half years, in dire poverty. We had nothing to eat, since the lady only had one ration card for the three of us – my mother could no longer use hers, it was marked Jewish on it. She was exceptional, she was a Righteous.

Once Mom risked her life to take me to the hospital because she noticed that my bones were deformed. She had a Jewish friend who had a Catholic friend. The latter made an appointment at the Bretonneau hospital in the 17th arrondissement of Paris, so that I could have an orthopedic corset in order to fit in this cubicle until the end of the war. He put me in a truck at 5 a.m. We waited for the doctor to arrive. We entered the consultation, they explained that I was living in difficult conditions, the doctor put his hand on the phone and told them that if we did not leave immediately, he would call the Kommandantur. He also told them that I did not need an orthopedic corset since, anyway, I would burn in the crematoria.

The Return of Mordka

My father, on his way back, spoke to a cousin who ran a shoe store in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine. We lived with Mom in a hotel, where she could work at night on a Singer machine. The cousin came with the news that Dad was alive. We were overjoyed. I had the image of Dad before the war. A gentleman arrived, very skinny, in a black suit. I stuck to the bedroom wall and shouted, “That’s not my daddy. I want my dad”. My parents were crying. There was nothing to do, I didn't want him to touch me, to approach me. He stayed with us at the hotel, but I wasn't getting used to him. One day he slit his throat. I didn't recognize him, the people he told about the camps didn't believe him, said he was exaggerating. We treated him at the Bichat hospital, that of the deportees, he recovered. I understood that this dad who had existed would no longer exist. We got used to it. Step by step. He never wanted to be a hairdresser again, he had been a hairdresser in Auschwitz. He was hired as a tailor. He recovered with difficulty. He only lived with the deportation. He spent his time receiving deportees, talking about the deportation. If we were talking about something else, he would say 'what are you talking about? of your banalities?’. He remained in front of the window to look, he only saw horrible things. After all that, it's hard to believe in God.

All reproduction prohibited